What happens when you cook your meat?

Meathead

Hot air cooks the surface of meat, but it cannot penetrate, so the energy built up on the outside of the meat moves slowly towards the center, eventually cooking the meat throughout. It moves slowly because meat is typically about 75% water and 5% fat. Great insulators. As the internal temp of your meat rises, its color is not the only thing that changes. A number of chemical and physical reactions take place, as the molecular structure of proteins and fats are altered by heat.

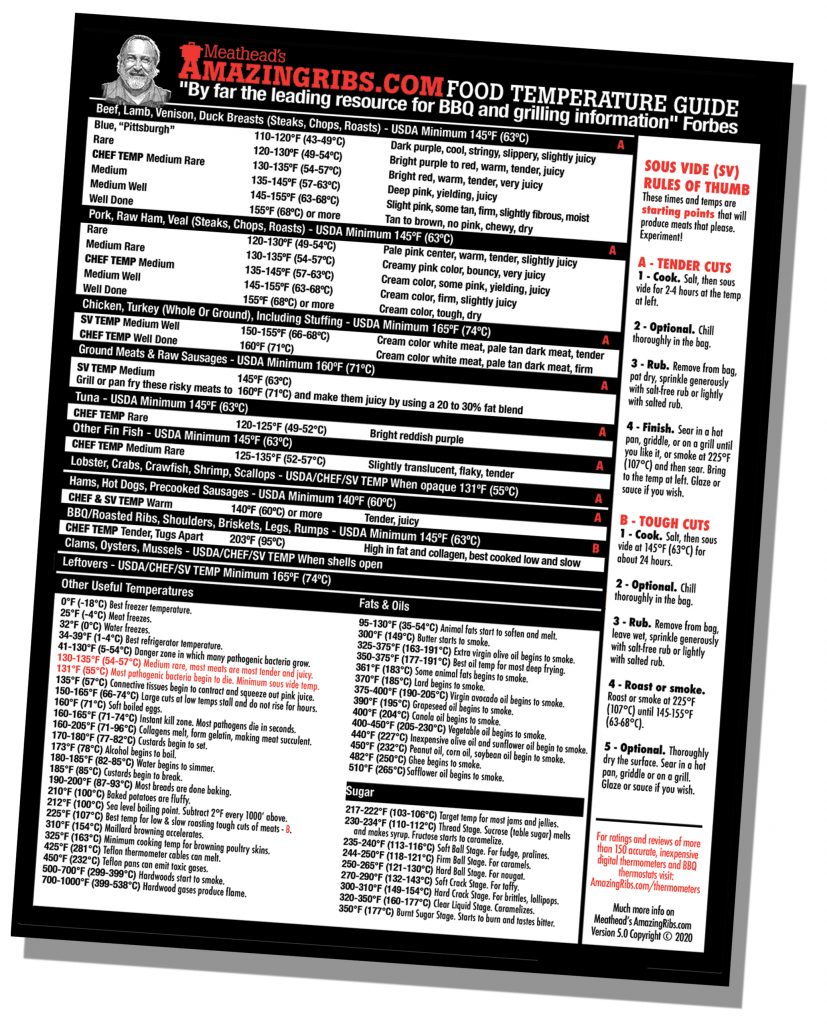

Here’s a guide to what happens. The meat temps shown here are approximate because other variables come into play such as the age of the animal, acidity, salt content, type of heat, humidity, etc. You can order an 8.5 x 11-inch magnet with a complete guide to more than 80 benchmark temperatures for meats (both USDA recommended temps, as well as the temps chefs, recommend), fats and oils, sugars, sous vide, freezer, and fridge temps, eggs, collagens, wood combustion, breads, and more. It won the National BBQ Association’s new product of the year award when it was introduced and it has been improved annually since. Order it from https://amazingribs.com/magnet

25°F (-4°C). Meat freezes. Meat starts to freeze at a lower temperature than water because water in meat is combined with proteins. Water expands as it freezes and sharp-edged crystals form that can rupture cell walls, creating “purge” when the meat is thawed, which is a spilling of liquid, mostly the pink fluid protein called myoglobin. Faster freezing makes smaller crystals, resulting in less purge.

34-39°F (1-4°C). Ideal refrigerator temperature. Water is not frozen, and microbial growth is minimized. You do have a good refrigerator thermometer don’t you?

41-130°F (5-54°C). The “USDA Danger Zone,” in which many pathogenic bacteria grow, sometimes doubling in number in as little as 20 minutes. According to the USDA, cold foods must be stored below 41°F (5°C), and hot foods above 135°F (57°C). That’s why we shouldn’t leave meats sitting around to come to room temp.

60°F (15°C). When chilling cooked meat, liquid gelatin forms a solid gel called aspic. Gelatin happens when connective tissues that wrap muscle fibers and connect them to bones, called collagen, melt. Yep, it’s the same stuff they inject under your skin to hide wrinkles.

95-130°F (35-54°C). Animal fats start to soften and melt.

114°F (46°C). Myofibrillar proteins begin to gel, changing meat texture.

120°F (49°C). Myosin, a protein involved in muscle contraction within fibers, begins to lose its natural structure. It unwinds or unfolds, a process called denaturing. It starts to clump, gets milky, and begins firming up the muscle fibers. Purple meats, called “rare,” start turning red. Fish begins to flake, and parasites begin to die.

120-130°F (49-54°C). Most mammal meats are considered Rare at this temp.

125-135°F (52-57°C). Target temp for most seafood.

131°F (54°C). Many pathogenic bacteria begin to die, slowly at first, but as the temp rises, they croak more rapidly. Minimum safe temp for sous vide. At this temp, it takes more than two hours to pasteurize meat. At 165°F (74°C), it takes just seconds.

130-135°F (54-57°C). Medium Rare. Most mammal meats are at optimum tenderness, flavor, juiciness. If you eat your meat well-done, you need to snap out of it.

130-140°F (54-60°C). Fats begin to liquefy, a process called rendering. This is a slow process and can take hours if meat is held at this temp.

135-140°F (54-60°C). Optimum temperature for pork chops, steaks, and tenderloin.

135°F (57°C). Connective tissues called collagens begin to contract and squeeze out pink juice from within muscle fibers into the spaces between the fibers and out to the surface. Meat begins to get dry. Myoglobin, the pink protein liquid within muscle cells, denatures rapidly and red or pink juices begin to turn clear or tan and bead up on the surface. It is not blood!

135-145 (57-60°C). Most mammal meats at this temperature are considered Medium.

140°F (60°C). Recommended temp for heating precooked meats such as hot dogs and city ham.

145-155(°C). Most mammal meats at this temperature are considered Medium Well. Very little pink remains. Meat is pretty dry.

150°F (66°C). Actin, another protein important to muscle contraction in live animals, begins to denature, making meat tougher and drier still.

150-165°F (66-74°C). This is “the stall zone,” in which large cuts such as pork butt and beef brisket seem to get stuck for hours when cooked at low temperatures like 225°F (107°C). In this range, moisture evaporates and cools the meat like sweat on an athlete. Inexperienced cooks panic. Eventually, temps start rising again. Whew!

155°F (68°C). Known as Well Done, meats are overcooked at this internal temperature. Much moisture has been squeezed out, and fibers have become tough. Bacteria are killed in less than 30 seconds, but spores can survive to much higher temps.

155-160°F (68-71°C). Optimum temperature for chicken and turkey white meat.

160°F (71°C). Minimum safe temp for ground meats.

160-165°F (71-74°C). The “Instant Kill Zone.” Normal cooking temps kill microbes on the outside of meats rapidly, so solid muscle meats are not likely dangerous since contamination is almost always on the surface. But ground meats and poultry often have bad guys beyond the surface, so you must cook these meats beyond the instant kill zone. That’s why the recommended internal temp for ground meats is 160°F (71°C) and for poultry is 165°F (74°C). When you reheat foods, you should take them up to 165°F 75°C).

160-165°F (71-74°C). Optimum temperature for chicken and turkey dark meat.

165°F (74°C). Minimum temp for reheating leftovers.

160-205°F (71-96°C). Tough collagens melt and form luscious gelatin. The process can take hours, so low and slow cooking creates the most gelatin. Dehydrated muscle fibers begin to fall apart and release from the bones. Meat becomes easy to shred. Even though the fibers have lost a lot of water, melted collagen and fat make the meat succulent.

200-205°F (93-96°C). Target temp for pork butt, ribs, beef brisket, and beef ribs.

212°F (100°C). Water boils at sea level. Boiling point declines about 2°F for every 1000′ above sea level.

225°F (107°C). Ideal air temperature for “low & slow” cooking of meats high in connective tissue. It is high enough so water evaporates from the surface to help form the desired crust called “bark,” but low enough to get the most out of enzymes, collagen melting, and fat rendering.

230-234°F (110-112°C). Fructose begins to caramelize.

310°F (154°C). The Maillard reaction accelerates surface browning, which is caused by chemical changes in proteins and sugars and results in thousands of delicious new molecules. The Maillard reaction begins at lower temps, but really takes off at 310°F (154°C).

325°F (163°C). Minimum air temperature for cooking chicken and turkey so skin browns and fat renders.

338°F (109°C). Sucrose (table sugar) caramelizes.

350-375°F (177-191°C). Best oil temp for deep fat frying.

361°F (183°C). Some animal fats begins to smoke.

370°F (185°C). Lard begins to smoke.

425F (281C). Teflon thermometer cables can melt.

600-700°F (316-371°C). Flash point or fire point, the temperature at which smoke from burning fat can burst into flame. Never use water to extinguish burning fat. Smothering it works better.

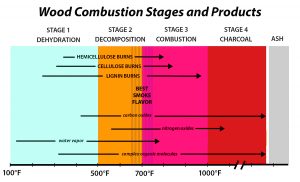

The four stages of wood burning

When wood is heated, it decomposes into water vapor, charcoal, and smoke. It goes through four stages. In a typical log burning pit all four stages can happen at once.

Stage 1 – Dehydration (100 to about 500°F). In this stage wood must be heated from an external source like a match, kindling, rolled up newspaper, or (horrors) lighter fluid. A lot of energy is consumed in evaporating the water. Until the wood dries out it cannot get much above 212°F. Steam and some gases like carbon dioxide are given off, but there is no flame or heat produced.

Stage 2 – Decomposition, gassification, and pyrolysis (500 to 700°F). Cellulose and lignin break down and boil off much like the water did in a gaseous cornucopia of volatile organic compounds and particulates. The gases will burn if there is an ignition source like a flame or spark, but they will not ignite on their own.

Stage 3 – Combustion (700 to 1,000°F). Escaping gases burst into flame. You can see this in a log in a fireplace as gases shoot out through cracks and they ignite and burn orange. Prof. Blonder calls this the “burning bush” stage. Other gases emerge, among them nitric oxide (NO) if there is sufficient oxygen. Nitric oxide is essential for formation of the smoke ring (page ???) in meat. In the sweet spot of about 650 to 750°F, the best aromatic compounds for cooking come off, among them guaiacol and syringol, which are primarily responsible for the aromas we like in smoke. Some are ethereal and dissipate, and that’s why barbecue doesn’t taste the same after it has been reheated. As the temperature rises above 750°F, acrid, bitter, and possibly hazardous compounds are formed.

Stage 4 – Charcoal formation (above 1,000°F). Most of the organic compounds have burned off leaving behind pure carbon, or char, which burns as red embers with little smoke, odor, and no flavor.

Meathead is the Barbecue Hall of Famer who founded AmazingRibs.com, by far the world’s most popular outdoor cooking website. He is the author of “Meathead, The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling” a New York Times Best Seller that was named one of the “100 Best Cookbooks of All Time” by Southern Living magazine. For 2,000+ free pages of great barbecue and grilling info, visit AmazingRibs.com and take a free trial in the Pitmaster Club.